Minimizing Regret

Hazan Lab @ Princeton University

The two cultures of optimization

by Elad Hazan

The standard curriculum in high school math includes elementary functional analysis, and methods for finding the minima, maxima and saddle points of a single dimensional function. When moving to high dimensions, this becomes beyond the reach of your typical high-school student: mathematical optimization theory spans a multitude of involved techniques in virtually all areas of computer science and mathematics.

Iterative methods, in particular, are the most successful algorithms for large-scale optimization and the most widely used in machine learning. Of these, most popular are first-order gradient-based methods due to their very low per-iteration complexity.

However, way before these became prominent, physicists needed to solve large scale optimization problems, since the time of the Manhattan project at Los Alamos. The problems that they faced looked very different, essentially simulation of physical experiments, as were the solutions they developed. The Metropolis algorithm is the basis for randomized optimization methods and Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithms.

To use the terminology of Breiman’s famous paper, the two cultures of optimization have independently developed to fields of study by themselves.

The readers of this particular blog may be more familiar with the literature on iterative methods. The hallmark of polynomial time methods for mathematical optimization are so called “interior point methods”, based on Newton’s method. Of these, the most efficient and well-studied are “central path following” methods, established in the pioneering work of Nesterov and Nemirovski (see this excellent introductory text).

On the other side of the world, the early physicists joined forces with engineers and other scientists to develop highly successful Monte Carlo simulation algorithms. This approach grew out of work in statistical mechanics, and a thorough description is given in this 1983 Science paper by Kirkpatrick, Gelatt, and Vecchi. One of the central questions of this area of research is what happens to particular samples of liquid or solid matter as the temperature of the matter is dropped. As the sample is cooled, the authors ask:

[…] for example, whether the atoms remain fluid or solidify, and if they solidify, whether they form a crystalline solid or a glass. Ground states and configurations close to them in energy are extremely rare among all the configurations of a macroscopic body, yet they dominate its properties at low temperatures because as T is lowered the Boltzmann distribution collapses into the lowest energy state or states.

In this groundbreaking work drawing out the connections between the cooling of matter and the problem of combinatorial optimization, a new algorithmic approach was proposed which we now refer to as Simulated Annealing. In more Computer Science-y terminology, the key idea is to use random walk sampling methods to select a point in the convex set from a distribution which has high entropy (i.e. at a “high temperature”), and then to iteratively modify the distribution to concentrate around the optimum (i.e. sampling at “low temperature”), where we need to perform additional random walk steps after each update to the distribution to guarantee “mixing” (more below). There has been a great deal of work understanding annealing methods, and they are quite popular in practice.

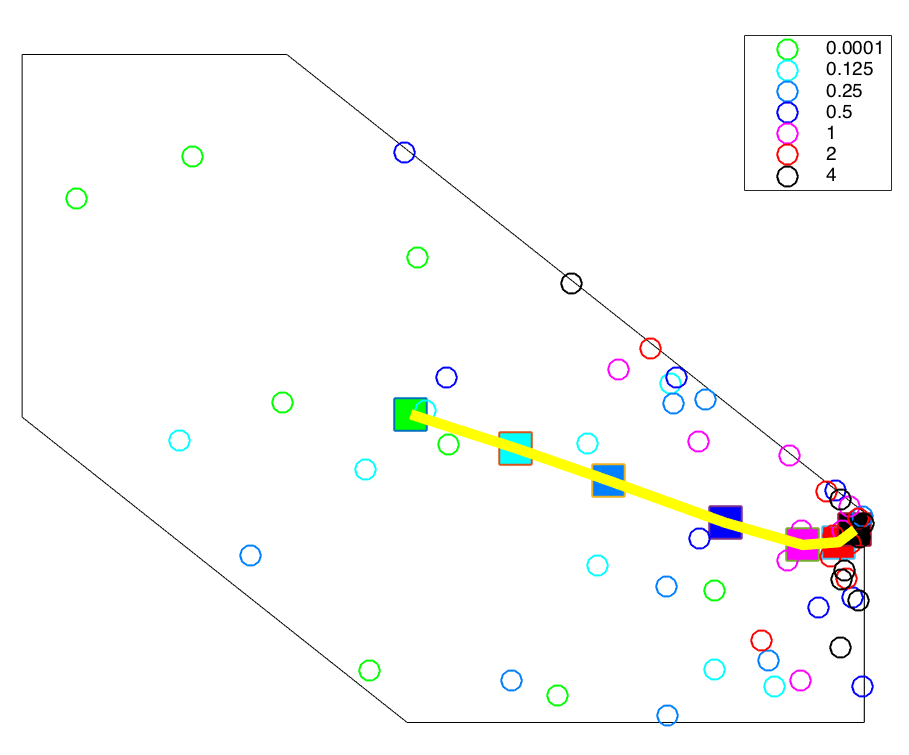

In a recent paper, we have discovered a close connection between the two methodologies. Roughly speaking, for constrained convex optimization problems, the iterates of Newton’s method lie on the same path as the means of the consecutive distributions of simulated annealing. This is depicted in the picture below. Besides the intriguing connection, this discovery yields algorithmic benefits as well: a faster convex optimization algorithm for the most general input access model, and a resolution of a open problem in interior point methods.

We continue with a more detailed description of path-following interior point methods, simulated annealing, and finally a discussion of the consequences.

An overview of the Statistical Mechanics approach to optimization

The Simulated Annealing approach to optimization is to reduce a given formulation to a sampling problem. Consider the following distribution over the set \(K \subseteq R^n\) for a given function \(f: R^n \mapsto R\). \(P_{f,t}(x) := \frac{\exp(- f(x)/t )} { \int_K \exp(-f(x')/t ) \, dx' }\). This is often referred to as the Boltzmann distribution. Clearly – as \(t\) approaches zero, this distribution approaches a point-mass concentrated on the global minimizer of \(f\).

The question is now – how do we sample from the Boltzmann distribution? Here comes the fantastic observation of the Los Alamos scientists: formulate a random walk such that its stationary distribution is exactly the one we wish to sample from. Then simulate the random walk till it mixes – and voila – you have a sample!

The Metropolis algorithm does exactly that – a general recipe for creating Markov Chains whose stationary distribution is whatever we want. The crucial observation is that simulating a random walk is many times significantly easier than reasoning about the distribution itself. Furthermore, it so happens that the mixing time in such chains, although notoriously difficult to analyze rigorously, are very small in practice.

The analogy to physics is as follows – given certain initial conditions for a complex system along with evolution rules, one is interested in system behavior at “steady state”. Such methods were used to evaluate complex systems during WWII in the infamous Manhattan project.

For optimization, one would use a random walk technique to iteratively sample from ever decreasing temperature parameters \(t \mapsto 0\). For \(t=0\) sampling amounts to optimization, and thus hard.

The simulated annealing method slowly changes the temperature. For \(t = \infty\), the Boltzmann distribution amounts to uniform sampling, and it is reasonable to assume this can be done efficiently. Then, exploiting similarity in consecutive distributions, one can use samples from one temperature (called a “warm start”) to efficiently sample from a cooler one, till a near-zero temperature is reached. But how to sample from even one Boltzmann distributions given a warm start? There is vast literature on random walks and their properties. Popular walks include the “hit and run from a corner”, “ball walk”, and many more.

We henceforth define the Heat Path as the deterministic curve which maps a temperature to the mean of the Boltzmann distribution for that particular temperature. \(\mu_t = E_{x \sim P_{f,t}} [ x]\) Incredibly, to the best of our knowledge, this fascinating curve was not studied before as a deterministic object in the random walks literature.

An overview of the Mathematics approach to optimization

It is of course infeasible to do justice to the large body of work addressing these ideas within the mathematics/ML literature. Let us instead give a brief intro to Interior Point Methods (IPM) – the state of the art in polynomial time methods for convex optimization.

The setting of IPM is that of constrained convex optimization, i.e. minimizing a convex function subject to convex constraints.

The basic idea of IPM is to reduce constrained optimization to unconstrained optimization, similarly to Lagrangian relaxation. The constraints are folded into a single penalty function, called a “barrier function”, which guaranties three properties:

- The barrier approaches infinity near the border of the convex set, thereby ensuring that the optimum is obtained inside the convex set described by the constraints.

- The barrier doesn’t distort the objective function too much, so that solving for the new unconstrained problem will give us a close solution to the original formulation.

- The barrier function allows for efficient optimization via iterative methods, namely Newton’s method.

The hallmark of IPM is the existence of such barrier functions with all three properties, called self-concordant barrier functions, that allow efficient deterministic polynomial-time algorithms for many (but not all) convex optimization formulations.

Iteratively, a “temperature” parameter multiplied by the barrier function is added to the objective, and the resulting unconstrained formulation solved by Newton’s method. The temperature is reduced, till the barrier effect becomes negligible compared to the original objective, and a solution is obtained.

The curve mapping the temperature parameter to the solution of the unconstrained problem is called the central path. and the overall methodology called “central path following methods”.

The connection

In our recent paper, we show that for convex optimization, the heat path and central path for IPM for a particular barrier function (called the entropic barrier, following the terminology of the recent excellent work of Bubeck and Eldan) are identical! Thus, in some precise sense, the two cultures of optimization have been studied the same object in disguise and using different techniques.

Can this observation give any new insight to the design of efficient algorithm? The answer turns out to be affirmative.

First, we resolve the long standing question in IPM on the existence of an efficiently computable self-concordant barrier for general convex sets. We show that the covariance of the Boltzmann distribution is related to the Hessian of a self-concordant barrier (known as the entropic barrier) for any convex set. For this computation, all we need is a membership oracle for the convex set.

Second, our observation gives rise to a faster annealing temperature for convex optimization, and a much simpler analysis (building on the seminal work of Kalai and Vempala). This gives a faster polynomial-time algorithm for convex optimization in the membership oracle model – a model in which the access to the convex set is only through an oracle answering questions of the form “is a certain point x inside the set?”.

tags:Share on: